Growing Up Between Two Worlds: Immigrant Roots and Hidden Struggles

Henry’s parents, Ilse Anna Marie (née Hadra) and Harry Irving Winkler, were German-Jewish immigrants who fled Nazi Germany and settled in New York. From early on, Henry existed between two worlds — the world of his parents’ survival and the world of a classroom where he consistently failed to read and keep up.

Behind the scenes, Henry was dealing with dyslexia — though he didn’t know it at the time. He was a bright, outgoing kid who could be the class comedian, but schoolwork was agony. His parents didn’t understand. The terms they used — “lazy,” “dummer Hund” (German for “dumb dog”) — seeped into his self-image.

He attended McBurney School and repeated geometry four times. When he finally graduated in 1963, the diploma arrived in the mail. No fanfare. Just relief.

From Frustration to Yale: The Theater Pivot That Saved Everything

Despite his struggles, Henry kept going. He applied to 28 schools and got into just two — one of them being the prestigious Yale School of Drama, where he earned an M.F.A. in 1970.

At Yale, he found something vital: a space where performing, improvising, and even forgetting lines meant creating something new. He once auditioned with a Shakespearean speech he couldn’t remember, so he improvised — and the school accepted him anyway. That moment shifted everything.

He later credited his time at Yale as the “critical foundation” for his career.

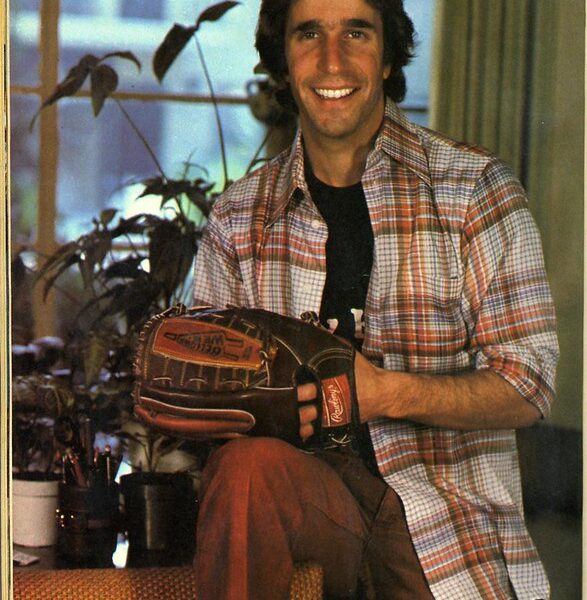

The Fonz Was Born — And So Was a Mask

In 1974 Henry landed the role that turned him into a cultural icon — Arthur “Fonzie” Fonzarelli on Happy Days. Initially a minor character, Fonzie evolved into the show’s center of cool.

What many didn’t know then: behind the swagger of Fonzie, Henry was grappling daily with reading scripts and making sense of words that twisted before his eyes. His dyslexia forced him to use every trick available — memorizing scenes, improvising when needed, leaning into character rather than script.

During that decade on TV, Henry shot to stardom. Yet at the same time he feared being typecast — a worry he acted on when he turned down the lead role in Grease because he didn’t want to be forever locked into one type of image.

The Discovery That Changed Everything

His nephew Jed was diagnosed with dyslexia when Henry was 31. For the first time, Henry realized: this is what I had too. The diagnosis freed him. It changed how he thought about himself, his childhood, his work. He became not just an actor, but an advocate.

In the years that followed, Henry co-wrote the children’s book series Hank Zipzer, about a dyslexic youngster. He used a dyslexia-friendly font in prequel editions. He became a voice for kids who, like him, were told they were “dumb” when all they needed was understanding.

Reinvention, Risk, Legacy — A Career That Refused to Stop

After Happy Days ended in 1984, Henry found himself battling typecasting. He was known as The Fonz, and that made many others hesitant to cast him in new ways. But the same resilience that carried him through childhood carried him through this.

In later decades, he starred in shows like Arrested Development and earned wide acclaim for Barry, a role that finally got him a Primetime Emmy in 2018 for Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Comedy Series.

Henry’s work behind the camera — producing, directing, writing — showed that he didn’t rest on his early success. In his own words, he was determined to be more than The Fonz.

What Henry’s Life Teaches Us

Here’s what I draw from Henry’s journey — and why his story matters beyond fame or nostalgia:

1. A diagnosis doesn’t define you — but understanding it can free you

Henry might never have reached this level of self-acceptance if he didn’t face his dyslexia. Once he did, he used it as fuel rather than a barrier.

2. Reinventing yourself is possible at any stage

He went from high-school struggler to Yale-trained actor to television star to children’s author and award-winning character actor. The arc didn’t end when the Fonz era did — if anything, it deepened.

3. Success doesn’t negate pain

Even as Fonzie became a symbol of effortless cool, Henry was still the kid called “dummo Hund,” still the teen grounded for failing math. Fame didn’t erase the scars, but he used them.

4. Use what you’ve learned to help others

Henry’s children’s books aren’t just stories — they’re tools. They were created to help kids with dyslexia feel seen. That makes his legacy more than entertainment.

Where Henry Winkler Ends Up

Now in his late 70s, Henry continues to act, write, advocate, and remind people that the story of your life doesn’t have to be written by someone else. He still shows up, still works, still cares. He even revisited his heritage on the show Better Late Than Never, when in Berlin he found the memorial brass “stolperstein” for his uncle who died in the Holocaust — a deeply personal moment of reckoning for his immigrant roots.

Henry once said: “I never had a Plan B.” That’s not bravado; it’s truth. He leaned into acting because nothing else made sense. But once he found what he was good at — and why — he shaped his career around that.

It’s a story worth sharing, not only for its celebrity appeal but for its profound message of resilience and triumph over life’s obstacles!